The alewives are back and thriving, and so is the West River Nature Preserve.

Proof of the success of removing the Pond Lily dam in the West Rock section of New Haven a few years ago is that the number of fish counted this year in Save the Sound’s trap in Woodbridge almost quadrupled last year’s record, with 200 swimming up the West River to spawn in Konolds Pond. The importance of the rejuvenation has been noted by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Last year, Save the Sound, an environmental agency, counted 53 all season. But this year, on April 22, “56 moved through and into the trap in one day,” said Jon Vander Werff, fish biologist for Save the Sound. “I was shocked in one day that we beat the [2020] number.”

Water flowing in the West River after the demolition of the Pond Lily Dam, 2016.

Arnold Gold / Hearst Connecticut MediaIt takes three to five years for alewives to reach sexual maturity, so this year’s count really showed results of returning the river to its natural state. In addition, “we’re seeing no net loss of wetland,” Vander Werff said, just a shift from wetlands that are always underwater to those that are wet part of the year.

That, in turn, has brought back a lush amount of foliage, with at least 88 species of plants thriving, such as Joe-Pye weed, which is good for pollinators as well as for erosion control. Along the West River, it grows as high as 8 feet. Other vegetation has been planted, in a cooperative project with the greenhouse program for people with disabilities at Edgerton Park.

Combined with 1,000 alewives that were seeded from Bride Pond in East Lyme, there are 1,200 spawning in Konolds Pond in Woodbridge, more than three-quarters of a mile upstream from where the dam once blocked the river’s flow near the Walgreens on Whalley Avenue, according to the agency.

Not only that, “this is the third year in a row we’ve gotten a sea lamprey in the trap,” Vander Werff said. They’re parasitic, jawless fish that attach to other fish, suck their blood and play “a vital role in the ecosystem for other fish eating them,” as well as their larvae, known as ammocoetes.

Save the Sound also built a line of stones across the river that keeps the water level upstream from dropping and protects a wooden bridge’s pilings.

“This riffle is where the … sea lamprey ammocoetes were utilizing as habitat for becoming adults,” Vander Werff said. “Out of the entire river, they selected a spot that was engineered to become adults. We must be doing something right.”

The alewives are anadromous fish, meaning they live in saltwater but enter fresh water to spawn, like salmon. They swim upstream from Long Island Sound and the juveniles will swim back, some into the Atlantic Ocean, Vander Werff said. “They spawn in wetlands and ponds and slow water,” he said. “The dam was a barrier for them to access adequate spawning grounds.”

The alewife population had been declining “up and down the Eastern Seaboard,” Vander Werff said. It was the result of habitat loss, including dams and development, overfishing and pollution, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

“The population in entirety is doing better, but it’s doing better from extremely low, devastated numbers,” he said.

The native perennial, Joe-Pye weed, thrives along the banks of the West River in New Haven on June 23, 2021 in an area that the Pond Lily dam once stood.

Arnold Gold / Hearst Connecticut MediaIn addition to Pond Lily, Save the Sound has removed dams on Whitford Brook in Mystic and the Quinnipiac River in Meriden and Southington, according to its website.

“There’s no way we can have robust sport-fishing populations if there’s no food for them,” Vander Werff said.

The 132-food Pond Lily dam, with its 80-foot dilapidated spillway, dating back to 1794, served as a water source for a grist mill at one time. But for the alewife and blueback herring in the West River, “their population was really being destroyed,” Vander Werff said.

Before the dam was removed in the winter of 2015-16, there was a fish ladder to help the alewives swim upriver, “but it fell into disrepair,” Vander Werff said.

Jon Vander Werff, fish biologist with Save the Sound, stands in front of a diadromous fish research trap at Konold's Pond in Woodbridge on June 23, 2021. The trap allows Vander Werff to obtain estimates of fish populations and the times that they swim upstream to spawn.

Arnold Gold / Hearst Connecticut Media“This was a really important one because of the Green Corridor in New Haven and up into Woodbridge,” he said. “Because where they were spawning wasn’t adequate. There wasn’t a lot of young reaching adulthood.”

Once the alewife larvae grow into juveniles, they swim down to Long Island Sound. Not all will make it though. The fish, also known as menhaden and river herring, are an important part of the food chain. In the rivers and ponds, they are eaten by large- and smallmouth bass and river trout, as well as raccoons, snapping turtles and birds such as great blue herons and osprey.

Out in the Sound and the ocean, the fish are food for cod, striped bass, tuna and haddock. Anglers use them for bait.

In addition to the alewives, Vander Werff said, “I have surveyed gizzard shad here. Also brook trout, which is really exciting,” and an American eel, “the size of your arm.”

The funnel trap built at the bottom end of 74-acre Konolds Pond, made out of PVC pipe, rebar, aquaculture netting “and a lot of zip ties,” caught its last straggler June 10, Vander Werff said. Alewives are a protected species and are quickly returned to the water.

“I think it’s fantastic,” said Suzanne Paton, supervisory fish and wildlife biologist for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in Charlestown, R.I. The agency helped finance the dam removal with $661,500 in federal money distributed after Superstorm Sandy in 2012.

“It was really important for the Fish and Wildlife Service to understand how quickly the fish populations would recover. … We’re trying more and more to restore the channel to its historic state,” Paton said.

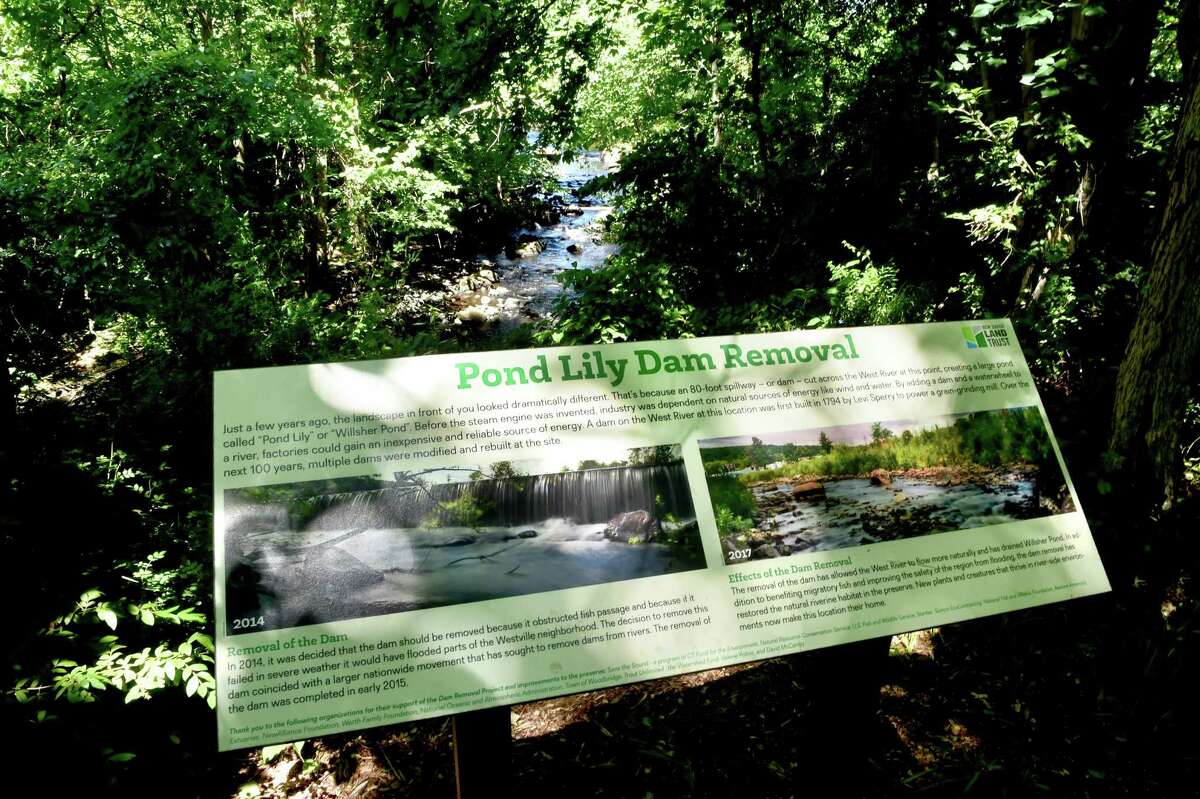

A sign near the West River in New Haven on June 23, 2021 details the history of the Pond Lily dam, it's removal and the effects of the removal.

Arnold Gold / Hearst Connecticut MediaShe said the agency also has supported monitoring of the fish populations in Pond Lily and Hyde Pond in Ledyard, from which the Mystic River flows.

Vander Werff didn’t want to predict what will happen next year, but he’s confident the alewives are back to stay.

“These fish are miraculous,” he said. “As soon as you help them the slightest bit, they bounce back insane.”

edward.stannard@hearstmediact.com; 203-680-9382

June 27, 2021 at 06:05PM

https://ift.tt/3y3xdPH

'These fish are miraculous': Rejuvenation of New Haven river lauded by scientists - New Haven Register

https://ift.tt/35JkYuc

Fish

No comments:

Post a Comment